- Sophia Shalmiyev Mother Winter

- Sophia Shalmiyev Husband

- Sophia Shalmiyev Interview

- Sophia Shalmiyev Mother Winter

From its first pages, Mother Winter by Sophia Shalmiyev (Simon & Schuster) rejects the notion that a human life, particularly one touched by trauma, can be captured in a tidy arc. “Russian sentences begin backward,” its first line announces, a signpost to readers who might expect a more conventional memoir. However, it’s not sentences but blocks of text, and the white space between them, that shape this story. In the third paragraph, Shalmiyev introduces her daughter before mentioning her own mother, but she doesn’t linger. We move through a narrative that, from one vignette to the next, leaps in time, rarely allowing us to remain in a scene for more than a beat.

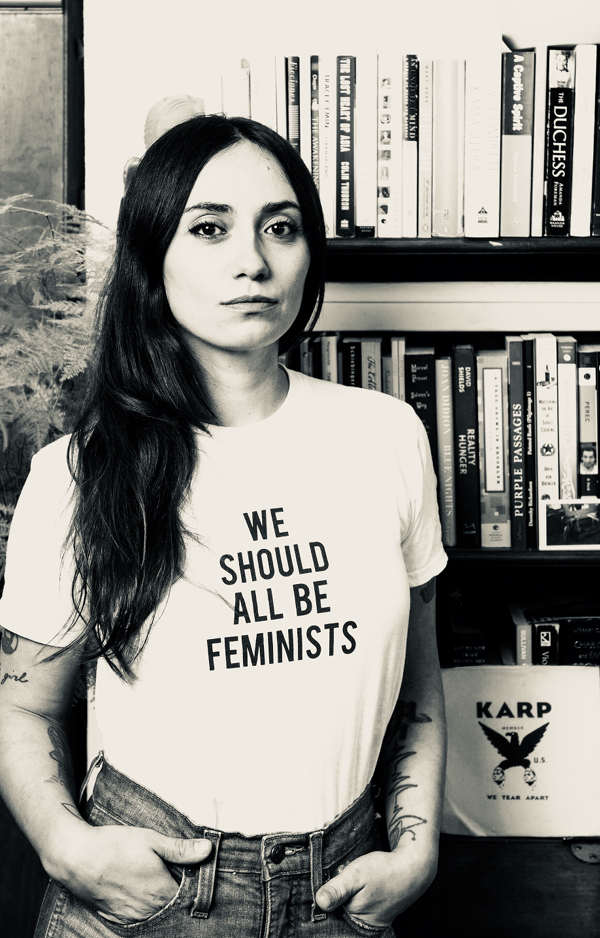

1,921 Followers, 6,122 Following, 3,514 Posts - See Instagram photos and videos from Sophia Shalmiyev (@sshalmiyev). Sophia Shalmiyev Photo: Thomas Teal In her debut memoir Mother Winter, Sophia Shalmiyev creates a haunting, lyrical meditation on her absent mother, a troubled alcoholic whom Shalmiyev and her. Sophia Shalmiyev emigrated from Leningrad to America in 1990. She is a feminist writer and painter living in Portland with her two children. Mother Winter (Simon & Schuster, 2019) is her first book. Sophia Shalmiyev is on Facebook. Join Facebook to connect with Sophia Shalmiyev and others you may know. Facebook gives people the power to share and makes the world more open and connected.

In forgoing linear structure, Shalmiyev strives to find new ways to represent an experience that resists easy comprehension: a mother’s abandonment of her child, who then leaves her mother—and motherland—before becoming a mother herself. Stitching these fragments with complexity and nuance, she challenges the authorial/maternal urge to provide “structure and order within the chaos,” calling into question our “propensity for false pattern recognition, to look for meaning, a belief system when mystery is too anxious of a box to contain us—a story that can signify a completeness we have only felt in the darkness of our mother.”

Nonetheless, readers may piece together a loose chronology. Sophia is born in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in the late 1970s to Gabriel, an Azerbaijani Jewish man, and Elena, a Russian alcoholic. Sophia’s parents divorce when she’s in first grade; after a custody battle, she’s sent to boarding school. When at home with her father, there is a “lack of money, lack of food,” and she’s “unkempt and smelly,” with “no one to make me take a bath on Sunday nights.” She writes: “The decade is a bronze disease patina, the green paste on a doorbell that rings when you show up, and you do not show up very often,” speaking to her mother in a direct address that weaves throughout the story, reminiscent of Kiese Laymon’s Heavy and Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. In 1990, Gabriel flees the Soviet Union with eleven-year-old Sophia, leaving behind his estranged ex-wife. Sophia comes of age—first in Italy, where she endures a sexual assault, then in Brooklyn—“elaborately motherless.” She attends college in Olympia, Washington, at the height of the riot grrl movement, a formative step in her journey as an artist that only hints at her preceding teenage years, largely excised from the story. After traveling to Russia, a trip that yields no closure, she cheats on her boyfriend with Mike, her future husband, with whom she’ll have two children.

Sophia Shalmiyev Mother Winter

Sophia Shalmiyev Husband

Echoing her recursive obsession with numerology, Shalmiyev repeatedly uses figurative language to define something she’s already defined, especially her mother. It highlights her struggle to make sense of her experience, her inability to pin down the psychic presence of a parent who is first absent, then lost altogether. Elena is gorgeously described as “a pantry-moth mother. Stuck mottled in sacks of grain”; “a mythical beached mermaid swimming home from the bar in the dark”; “a north wind madness kicking me around”; “an armless, white marble statue found at the bottom of the sea”; “a crater in between giving up and looking again”: “an impulse purchase from the discount mall”; “a cut flower, a bloom crinkling brown on one end and a closed stalk with no water to drink.” The titular metaphor recurs, its inherent uncertainty making it the only symbol that sticks:

Sophia Shalmiyev Interview

You’ll never know how bad she’ll be, or when she’s coming or going… Mother winter is all surface beauty. Want to lick her like buttercream icing, like glistening egg whites beaten for a birthday cake. But cold slows us down and makes us sleepy until we are high and hallucinating, then give in and take a permanent nap.

Similarly, Shalmiyev tries to make meaning out of motherhood, but every attempt to generalize is filtered through the specificity of her own loss. Her images of emptiness aren’t necessarily universal: a mother is a “sieve,” a “circle—a complete and perfect hole,” and, citing the Japanese word ma, a “gap, pause, or space between two structural parts.” The only possible maternal identity, it seems, is the lack of any at all.

With this dark outlook colored by her experience, it’s surprising when Sophia chooses to have children, though we know it’s coming. Her decision is rooted in the body, a physical reconciliation after years of dissociation. Early in the book, she says, “I could buy the ticket, take the ride, but never arrive at my body, clean and fed. Not until I cleaned and fed children of my own.” Later, she writes: “After I couldn’t find my mother…I only had the drive to make life where mass graves were dug up in my body.” With Mike, “I smelled our future children’s dandelion scalps shedding in the bath all by laying my head on him.” She recounts the grueling physicality of childbirth, miscarriage, nursing, and caring for a newborn while wearing “adult diapers,” in a body transformed, with breasts that are “wads of chewed-up gum spat out on the sidewalk…so well used they have become public.” By reconnecting with her body, “becom[ing] too busy raising children to go back to Russia again and be dissatisfied with the search and its outcomes,” there’s an ironic note of healing in no longer having to “travel for pain.” But as a mother, she never achieves closure: worrying that she, too, is destined to flee; feeling her children are “contaminated” by her family’s history; even her daughter’s hair, reminiscent of Elena’s, stings of “rejection.”

Maybe that’s the whole point of conception. When offered only commas and ellipses you will bust your tail to find a period; a full stop. Then your train never comes, and you wonder how to get home. You went to your old train stop like a fool and it is now permanently under construction.

Only through the act of bringing language to her experience—the “gestation of words” that “[spin] out a new life,” like her sewing machine—does Shalmiyev begin to mend her sense of loss. In Elena’s absence, Sophia fashions a new feminist lineage, her own “fantasy caretaker army,” which includes Audre Lorde, Dorothy Richardson, Renata Adler, Sappho, Anaïs Nin, and Chris Kraus. While writing memoir is an act of exposure that makes her, in the eyes of some, “an appalling elegist of limbos, provoking spectators, for shame,” her art provides a necessary outlet that allows her to stay present as a parent: “I only leave them for a few hours to write about her leaving for good.”

In its lyricism, fragmentation, and exploration of the body, Mother Winter is a feminist memoir of its moment, easily shelved alongside Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts and Carmen Maria Machado’s In The Dream House. Shalmiyev’s uneasy truths may not be universal, but it’s riveting to read a story that adds complexity to the expanding canon of motherhood narratives, and to bear witness to an act that still feels defiant: for a mother to leave her children, albeit temporarily, to craft a narrative that might shape a world outside the domestic sphere.

Sophia Shalmiyev Mother Winter

***